Table Of Content

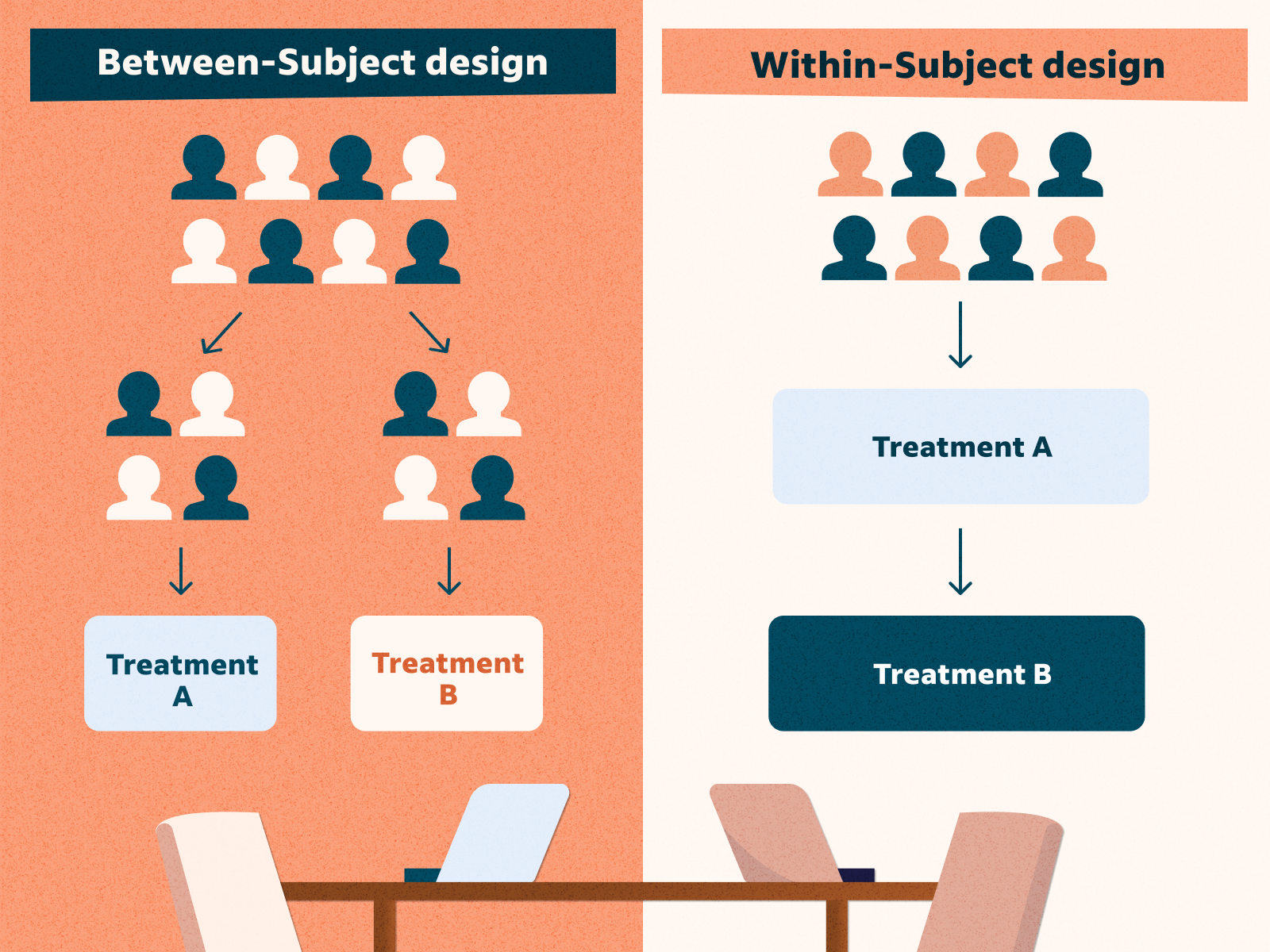

The between-subjects design is conceptually simpler, avoids order/carryover effects, and minimizes the time and effort of each participant. Just as including multiple levels of a single independent variable allows one to answer more sophisticated research questions, so too does including multiple independent variables in the same experiment. But including multiple independent variables also allows the researcher to answer questions about whether the effect of one independent variable depends on the level of another.

Main Effects and Interactions

In practice, however, one single study often serves more than one purpose (Schoonenboom et al. 2017). The more purposes that are included in one study, the more difficult it becomes to select a design on the basis of the purpose of the investigation, as advised by Greene (2007). Of all purposes involved, then, which one should be the primary basis for the design?

Book traversal links for 13.3 - The Two Factor Mixed Models

Another important use of complex correlational research is to explore possible causal relationships among variables. This might seem surprising given that “correlation does not imply causation”. It is true that correlational research cannot unambiguously establish that one variable causes another. Complex correlational research, however, can often be used to rule out other plausible interpretations. Importantly, the effect of the gas variable on driving depends on the levels of having a key. Or, to state it in reverse, the effect of the key variable on driving depends on the levesl of the gas variable.

Assigning Participants to Conditions

Design of complex neuroscience experiments using mixed-integer linear programming - ScienceDirect.com

Design of complex neuroscience experiments using mixed-integer linear programming.

Posted: Wed, 05 May 2021 07:00:00 GMT [source]

The typologies were designed to classify whole mixed methods studies, and they are basically based on a classification of simple designs. Complex designs are sometimes labeled “complex design”, “multiphase design”, “fully integrated design”, “hybrid design” and the like. This problem does not fully apply to Morse’s notation system, which can be used to symbolize some more complex designs. The area around the center of the [qualitative-quantitative] continuum, equal status, is the home for the person that self-identifies as a mixed methods researcher. This researcher takes as his or her starting point the logic and philosophy of mixed methods research.

The data collection in this example was conducted simultaneously, and was thus concurrent – the quantitative closed-ended questions were embedded into the qualitative in-depth interviews. In contrast, the analysis was dependent, as explained in the next paragraph. Something similar applies to the classification of the purposes of mixed methods research. The classifications of purposes mentioned in the “Purpose”-section, again, are basically meant for the classification of whole mixed methods studies.

Two case studies

In the mixed methods literature, the distinction between sequential and concurrent usually refers to the combination of concurrent/independent and sequential/dependent, and to the combination of data collection and data analysis. We call two research components dependent if the implementation of the second component depends on the results of data analysis in the first component. Two research components are independent, if their implementation does not depend on the results of data analysis in the other component. Often, a researcher has a choice to perform data analysis independently or not. A researcher could analyze interview data and questionnaire data of one inquiry independently; in that case, the research activities would be independent. It is also possible to let the interview questions depend upon the outcomes of the analysis of the questionnaire data (or vice versa); in that case, research activities are performed dependently.

1. Multiple Dependent Variables¶

In practice, it is unusual for there to be more than three independent variables with more than two or three levels each. If one of the independent variables had a third level (e.g., using a handheld cell phone, using a hands-free cell phone, and not using a cell phone), then it would be a 3 × 2 factorial design, and there would be six distinct conditions. Notice that the number of possible conditions is the product of the numbers of levels. A 2 × 2 factorial design has four conditions, a 3 × 2 factorial design has six conditions, a 4 × 5 factorial design would have 20 conditions, and so on.

About

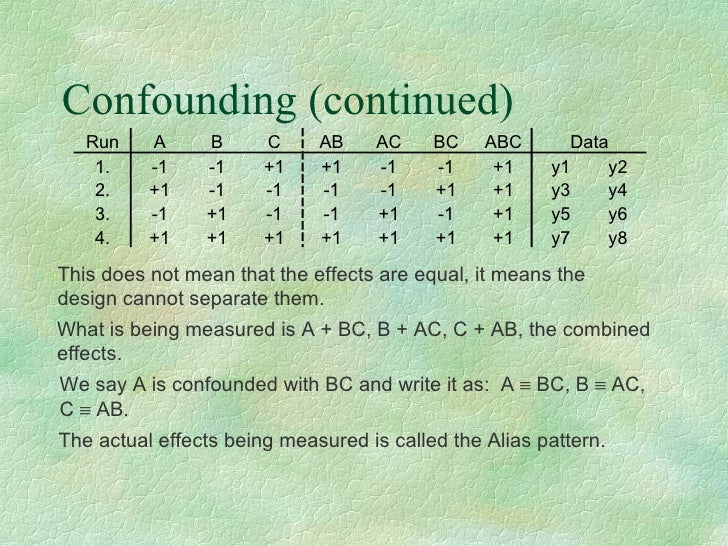

In a simple within-subjects design, each participant is tested in all conditions. In a factorial experiment, the decision to take the between-subjects or within-subjects approach must be made separately for each independent variable. In a between-subjects factorial design, all of the independent variables are manipulated between subjects.

First, non-manipulated independent variables are usually participant background variables (self-esteem, gender, and so on), and as such, they are by definition between-subjects factors. For example, people are either low in self-esteem or high in self-esteem; they cannot be tested in both of these conditions. An example is a study by Halle Brown and colleagues in which participants were exposed to several words that they were later asked to recall (Brown, Kosslyn, Delamater, Fama, & Barsky, 1999)[1]. Some were negative health-related words (e.g., tumor, coronary), and others were not health related (e.g., election, geometry).

Due to the decisive character of the core component, the core component must be able to stand on its own, and should be implemented rigorously. When we use a 2×2 factorial design, we often graph the means to gain a better understanding of the effects that the independent variables have on the dependent variable. This is important because, as always, one must be cautious about inferring causality from correlational studies because of the directionality and third-variable problems. For example, a main effect of participants’ moods on their willingness to have unprotected sex might be caused by any other variable that happens to be correlated with their moods. The simplest way to understand a main effect is to pretend that the other independent variables do not exist.

For this mixed-factorial design, we need to account for the fact thatwe have multiple observations coming from each person, so we will add arandom-effect of “subID”. After accounting for this statisticaldependence in our data, we can now fairly test the effects of Age Group,and Condition with residuals that are independent of each other. Again, for our purposes, the critical thing to note is that theF-values for the main-effects and interactions are the same between ourRM ANOVAs and the mixed-effects model. Without delving into themathematical details, this is a good demonstration that the appropriaterandom-effects our regression model make it analogous to the factorialANOVA. This allows us to capitalize on the benefits of mixed-effectsregression for designs that we would normally analyze using factorialANOVA.

However, I would stronglyencourage you to develop a more detailed understanding of general-linearmodels before jumping into mixed-effect models. For this example, we will focus on only the effect of condition, sowe will use the data_COND dataset to average across different trials.First, let’s plot the data to get a better sense of what the data looklike. As expected, we see that the average height is 1 inch taller when subjects wear shoes vs. do not wear shoes.

No comments:

Post a Comment